“[PUBLIC FINANCING OF ELECTIONS IS DESIGNED] TO REDUCE THE DELETERIOUS INFLUENCE OF LARGE CONTRIBUTIONS ON OUR POLITICAL PROCESS, TO FACILITATE COMMUNICATION BY CANDIDATES WITH THE ELECTORATE, AND TO FREE CANDIDATES FROM THE RIGORS OF FUNDRAISING.”

Citizen Funding of Elections

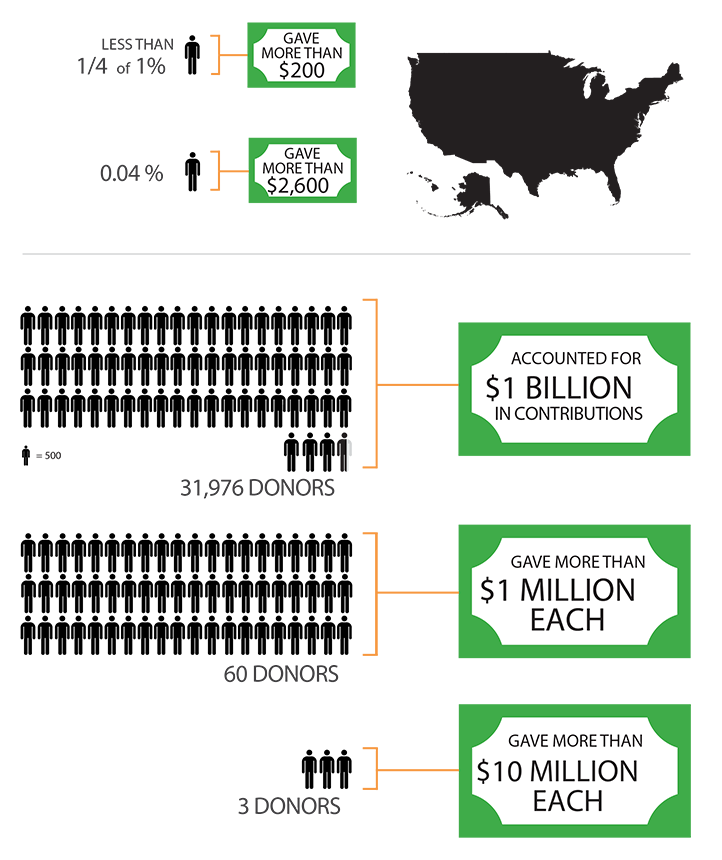

According to the Center for Responsive Politics (CRP) and the Sunlight Foundation, nonpartisan nonprofit organizations, less than one quarter of one percent of the U.S. population gave more than $200 in individual contributions in federal elections in the 2014 election cycle, while 0.04 percent gave contributions in excess of $2,600.5 In fact, CRP and Sunlight report that “31,976 donors—equal to roughly one percent of one percent of the total population of the United States—accounted for an astounding $1.18 billion in disclosed political contributions at the federal level.” Diving deeper into the numbers, they found that “[a] small subset—barely five dozen—earned the (even more) rarefied distinction of giving more than $1 million each. And a minute cluster of three individuals contributed more than $10 million apiece.”

U.S. POPULATION: 2014 FEDERAL ELECTION CAMPAIGN CONTRIBUTIONS

What this means is most Americans take no part in providing financial support to their preferred candidates, super PACs or any other type of political committee, whether because they cannot afford even a small donation or because they believe that a small donation is a meaningless drop in the flood of money made up of large contributions provided by very few people. The corollary is that candidates feel compelled to spend a large percentage of their time fundraising from these large donors prior to the election and being responsive to them after the election. The result is that those who can give or raise hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars—“bundlers”—hold a tremendous amount of power in our political system, while average citizens end up marginalized.

% OF AMERICANS WHO SUPPORT CITIZEN FUNDING

Citizen funding systems provide monetary support to political candidates. Some refer to these systems as “public financing,” but many reformers find the phrase laborious and bureaucratic. Citizens are the real agents of democracy in this country and should be recognized as such. These programs provide the vast majority of Americans with an incentive to participate. Either by limiting the amount and type of fundraising a candidate can do or by providing constituents with funds to contribute as they please, the government is able to redirect a politician’s attention to citizens who cannot donate thousands of dollars to politics.

% OF AMERICANS WHO SUPPORT A FUNDAMENTAL CHANGE TO THE WAY WE FINANCE CAMPAIGNS

Many states and municipalities now provide some form of citizen funding option for at least some public offices, and a system has been available for eligible presidential candidates since 1976, with matching funds for contributions for the primaries and full public funding for the general election. Even though participation in the public funding system is optional, from 1976 until the 2000 election, every major party candidate utilized the matching fund program for the primaries and accepted full public funding for the general election. However, there were structural defects built into the system and the law was not updated as campaigns changed to incorporate advances in media and technology and as “independent” groups began to play a bigger role in elections. This ensured candidates would eventually decide to forgo what has become an outdated citizen funding system. Nevertheless, for two decades the federal system was a success. States and municipalities have continued to enact public funding programs, serving as laboratories for different types of systems. At the same time, bills have been introduced in Congress to make the presidential citizen funding system viable once again and to create systems for the House and Senate.

What is truly impressive about the continuing efforts to enact citizen funding is that it has often been pursued through citizen-driven referenda and ballot measures—demonstrating widespread support for these programs. One 2014 poll found two-thirds of Americans support such a system, and a 2015 poll from the New York Times and CBS News found that 85 percent of the country would support “fundamental change” to the way campaigns are financed.

“I GOT TO SPEND TIME WITH VOTERS, AS OPPOSED TO DIALING FOR DOLLARS OR TRYING TO SELL TICKETS TO $250-A-PLATE FUNDRAISERS. [CITIZEN FUNDING] WAS MUCH BETTER.”

Types of Citizen Funding

Click to enlarge

There are several types of citizen funding programs, ranging from so-called “Clean Elections” programs that provide qualified candidates with total citizen funding to those that simply provide tax deductions for small political contributions. Systems that provide full citizen funding are intended to reduce the opportunity for corruption while freeing politicians from the fundraising race. Programs that provide citizens with public money then match some multiple of the small contributions multiply the impact of these donations. These programs do so by providing a tax incentive for those capable of making small contributions, and are intended to limit the influence of large contributions while encouraging and empowering the average citizen to make a donation to the candidates of their choice. Programs that provide funding directly to participating candidates (e.g., Clean Elections, matching funds and vouchers) can also require participating candidates to agree to abide by certain conditions, such as limits on how much they can spend on their campaign and/or contribution limits that are lower than those imposed on nonparticipating candidates. Because spending limits cannot be constitutionally mandated, participation in these citizen-funding systems must be voluntary. The most common citizen funding programs are:

- Clean Elections (Or Full Public Funding): A flat grant is provided to fully fund a qualifying candidate who voluntarily participates in the program. The candidate will generally be required to demonstrate sufficient support to receive funding, such as by raising a threshold amount of small (e.g., $5) donations. The candidate may also have to agree to certain conditions, including not raising private contributions other than any amount needed to qualify, limiting the amount he or she spends to the amount of the grant, participating in candidate debates and an audit of campaign spending.

- Matching Public Funds: The government matches small private contributions that a candidate raises. Depending on the jurisdiction, contributions up to a set amount may be matched dollar for dollar or at some multiple, such as six dollars or more in public money being provided for every private dollar contributed. Generally, there is a limit on the size of the contribution that will be matched (e.g., up to $100). Some systems require the participating candidate to agree to certain conditions, which may include lower contribution limits than apply to nonparticipating candidates, overall limits on what the campaign can spend, participation in candidate debates or an audit of campaign spending.

- Vouchers: The government provides citizens or registered voters with vouchers that they can, in turn, use to make political contributions to candidates of their choice. Candidates can then redeem vouchers for campaign funds. This system does not require the contributor to use his or her own funds and then obtain a reimbursement and, therefore, can allow economically disadvantaged people to make small contributions to campaigns. Participating candidates may have to agree to certain conditions.

- Refunds: Individuals can make small contributions up to a certain amount and then apply for a refund from the government, which may be made immediately upon application. This system requires the individual to be able to initially make the contribution, but does provide him or her with a reimbursement.

- Tax Deductions and Tax Credits: Contributors may deduct from the taxes they owe, or receive a tax credit for, their political contributions up to a set amount. The contributor only sees the benefit when they pay their taxes and must have taxable income for the deduction to apply.

- Hybrid Systems: Any two or more of the above systems can be combined. For example, a matching fund system for small contributions can be used in the primary, while a full grant can be made available in the general election, as was done with federal public funding for the presidential election.

The goal is to design public funding to limit the potential corrupting influence of large contributions, encourage and empower small donors and make the campaign finance system more transparent, all while ensuring participating candidates are not at a disadvantage and have enough resources to run competitive campaigns.

“WHEN YOU THINK ABOUT CLEAN ELECTIONS, THE FIRST WORD THAT COMES TO MIND IS FAIRNESS, BECAUSE IT BRINGS ABOUT INCLUSIVENESS. IT ALSO BRINGS ABOUT A GOOD AMOUNT OF COMPETITIVENESS, AND IT OPENS IT UP IN DIVERSITY AS WELL.”

Elements of Public Funding

Public funding programs can be designed to reduce the influence of large contributions, facilitate communication by candidates with the electorate and free candidates from the rigors of fundraising. As noted, tax credits, tax deductions and refund programs for political contributions provide incentives for people to make contributions, but generally do not require any opt-in by the candidate. Public funding systems that do require participation by the candidate, such as Clean Elections, matching funds and voucher programs have the advantage of not only empowering small donors, but can also support a more comprehensive campaign finance system involving additional limits and requirements for candidates. Candidate participation in public funding may include some of the following elements:

Required small dollar fundraising to establish eligibility for the program;

Limits on what a participating candidate can spend on the campaign, including limits on a candidate’s use of personal wealth;

Lower limits on contributions to the campaign;

Prohibition on participating candidates soliciting soft money (unregulated) contributions;

Audit or review of campaign spending to ensure public funds are not misspent;

Special reporting requirements to provide greater transparency or

Candidate agreement to participate in debates.

Limitations on Public Funding

The Supreme Court has imposed two major limits on public funding programs. First, since candidate participation in public funding programs requires candidates to abide by rules that would be unconstitutional (according to the current jurisprudence) if unilaterally imposed by the government—such as limits on overall campaign expenditures or the candidate’s use of personal funds—such programs must be voluntary. The second limit, which is really a corollary of the first, is that nonparticipating candidates cannot be in any way penalized or disadvantaged by the decision not to participate in public funding.

“BEFORE PUBLIC FINANCING, TO GET DONATIONS YOU HAD TO CALL PEOPLE. THAT WOULD GO ON. YOU’D SPEND HALF OF YOUR TIME IN THE ELECTION CYCLE CALLING UP PEOPLE, RAISING MONEY INSTEAD OF GOING OUT AND KNOCKING ON DOORS. NOW, YOU’RE GETTING IT FROM THE PEOPLE AND HEARING WHAT THEY WANT AND NOT FROM SPECIAL INTERESTS.”

As a practical matter, requiring the system to be voluntary has the advantage of enabling the programs to require candidates abide by meaningful restrictions aimed at reducing the negative influence of large contributions, facilitating communication by candidates with the electorate, freeing candidates from the relentless burden of fundraising and empowering small donors. On the other hand, given the rise of so-called “outside money” in the form of super PACs, dark money groups and sham issue organizations pouring money into our elections, many candidates are nervous about agreeing to limits or any other rules that they feel may put them at a real financial disadvantage in an election. That is why any successful system must provide adequate funds for participants, and may also provide additional support for qualifying candidates near the end of the campaign to respond to outside spending.

The challenge has been made more difficult by the Supreme Court’s expansive view of the second limitation on public funding; that it not in any way burden a nonparticipating candidate. For example, although not limited to public funding, the Supreme Court has found unconstitutional provisions that increase the contribution limits for a candidate who is facing a wealthy self-financed candidate. In the context of Arizona’s public funding system, the Supreme Court also struck down a provision that provided a publicly funded candidate additional money to respond to campaign activities of privately financed candidates and independent expenditure groups.

These restrictions have made the development of truly effective public funding programs more challenging. The goal is to design public funding to limit the potential corrupting influence of large contributions, encourage and empower small donors and make the campaign finance system more transparent, all while ensuring participating candidates are not at a disadvantage and have enough resources to run competitive campaigns. But, it can and has been done. In fact, successful public funding systems already exist at the state and municipal levels, and there are intensive efforts underway to design new public funding systems.

It is important to note that public approval of these systems is and remains very strong anywhere they are implemented, such as in Maine, Arizona and Connecticut. Additionally, studies have found that they are effective at meeting their stated goals: broadening the donor pool, allowing public officials to hear from constituents, increasing the number and diversity of candidates running for office, reducing the influence of special interests and lobbyists and strengthening the connections between elected officials and their constituents.

“IT IS UNNECESSARY TO LOOK BEYOND THE ACT’S PRIMARY PURPOSE—TO LIMIT THE ACTUALITY AND APPEARANCE OF CORRUPTION RESULTING FROM LARGE INDIVIDUAL FINANCIAL CONTRIBUTIONS—IN ORDER TO FIND A CONSTITUTIONALLY SUFFICIENT JUSTIFICATION FOR THE $1,000 CONTRIBUTION LIMIT...TO THE EXTENT THAT LARGE CONTRIBUTIONS ARE GIVEN TO SECURE A POLITICAL QUID PRO QUO FROM CURRENT AND POTENTIAL OFFICE HOLDERS, THE INTEGRITY OF OUR SYSTEM OF REPRESENTATIVE DEMOCRACY IS UNDERMINED.”

Source Limits and Prohibitions

Contributions and Independent Expenditures

Some frame the goal of campaign finance reform as getting “money out of politics.” However, the reality is that effective political discourse through ads, publications, speeches and debates requires the expenditure of money. Therefore, it may be more realistic to focus on addressing the problems caused by the need for money in political campaigns. Look at it this way: The problem is not that candidates have to spend money to run for office, but how much they have to raise, who they have to raise that money from and what they must promise or do in return for that money. A campaign finance system that allows a candidate to fund his or her campaign by raising large contributions from individuals, corporations, labor unions and other interest groups will naturally limit who can run for office, resulting in the candidate being more responsive to these donors and increasing the opportunity for corruption.

The problem is not that candidates have to spend money to run for office, but how much they have to raise, who they have to raise that money from and what they must promise or do in return for that money.

One way to begin to address this problem is to limit the amounts an individual or political committee can contribute to a candidate, political party or PAC and to limit or prohibit contributions from corporations or labor unions. Contribution limits will encourage candidates to reach out to more constituents and feel responsive to a larger number of people. In addition, with reasonable limits, a voter who can only make a small contribution to a campaign—be it $10, $25 or $50—is more likely to feel a stake in the election and more likely to vote. The problem is that under the current system, many individuals who can only afford to make small contributions believe they are virtually meaningless.

Of course, contribution limits and prohibitions have to fit within the Supreme Court’s current constitutional analysis of the regulation of money in politics. In Buckley v. Valeo, the Court created a legal framework that distinguishes between contributions made directly to a candidate or political party and money spent by an individual independently of a candidate or political party. In its controversial decision, the Court said that when a person spends money on his or her own speech independently of a candidate, his or her First Amendment rights are at the highest, while the danger of corruption is at its lowest because the independence from the candidate made it less likely the expenditure would give rise to a potential quid pro quo arrangement. Therefore, a limitation on the amount an individual can spend independently of a candidate is unconstitutional. In contrast, the Court said that direct contributions to a candidate involve giving money to someone else to turn into speech, which is more of a symbolic act of support through association. At the same time, direct contributions raise the greatest concern for potential corruption because of the involvement of the candidate. Using this framework, the Supreme Court held that the government can limit the amount and sources of contributions to candidates, but cannot limit what an individual can spend independently of a candidate. The same concept was extended to corporations and labor unions in 2010 in Citizens United, though that decision was extremely close, with five justices in the majority and the remaining four dissenting. Additionally, Buckley not withstanding, the Citizens United decision was an aberration in the history of campaign finance law, and bucked the trend of more than 100 years of established case law, much of which was written by conservatives on the bench. Many scholars, judges and politicians decried the decision; Republican Senator John McCain (R-AZ) called it the Court’s worst decision ever.

% OF AMERICANS WHO DISAPPROVE OF SUPREME COURT CITIZENS UNITED RULING

Public opinion concurs: 80 percent of Americans disapprove of the decision, including supermajorities of Democrats, independents and Republicans. A 2015 New York Times/CBS News poll found that “Americans of both parties fundamentally reject the regime of untrammeled money in elections made possible by the Supreme Court’s Citizens United ruling,” and that “Republicans in the poll were almost as likely as Democrats to favor further restrictions on campaign donations.”

Nevertheless, even though the Court’s argument here seems far removed from what is going on in the real world, it is the framework within which we have to work, until that framework is changed.

Contribution Limits

Click to enlarge

Federal law limits how much an individual or PAC can give to a federal candidate per election, with the primary and general considered separate elections. For the 2016 election, an individual can give $2,700 per election to a candidate and a PAC can give $5,000 per election. An individual has separate contribution limits on what they can give to the political parties and PACs. (There is no limit on what an individual can give to a PAC that only makes independent expenditures, commonly referred to as a super PAC.) Up until 2014, there was also an aggregate limit on what a person could give to all candidates, political parties and PACs in an election cycle. However, in McCutcheon v. FEC, the Supreme Court struck down these aggregate limits. Nevertheless, the Supreme Court has never suggested that it is prepared to overrule its holding in Buckley that limits on contributions to candidates are constitutional. Therefore, contribution limits remain an important tool in a campaign finance system.

Many states have limits on what an individual can give directly to a candidate, political party or PAC that makes contributions to candidates, while some states do not limit contributions. States that do so have relatively wide discretion in setting limits. The Supreme Court in Buckley said that it is not the Court’s role to second-guess the legislative determination as to the appropriate limit on contributions to candidates. However, that discretion is not without its limits. In Randall v. Sorrell, the Supreme Court held that Vermont’s individual contribution limits, which ranged up to $400 per two-year election cycle depending on the office, were unconstitutional because, taken together with other restrictions on individual support for candidates, they effectively became a prohibition on contributions.

The limit should be low enough to give the public confidence that large contributions are not corrupting the election, while high enough to allow candidates to raise sufficient funds to run for office.

As there is wide, though not unlimited, discretion in setting contribution limits, it is important to consider not only the dollar amount of the limit, but also whether different limits should be set for different entities. The limit should be appropriate to the specific context, such as the nature of the race and the general cost of an average campaign for a specific office. For example, a limit for a county council race may be lower than the limit for gubernatorial race in the same state. The contribution limit may reflect the varying costs of running for office in different states. But, in the end, the limit should be low enough to give the public confidence that large contributions are not corrupting the election, while high enough to allow candidates to raise sufficient funds to run for office. Americans, wealthy or not, have a fundamental right to participate in the political process, including through contributions to campaigns. De facto bans on contributions should certainly trigger review by the courts, and reformers must be vigilant in avoiding such pitfalls.

As noted, contribution limits do not have to be a one-size-fits-all proposition. For example, you can have separate contribution limits set for what an individual can give to a candidate, political party and PAC, while political parties and PACs can have a different limit on what they can give to candidates or each other. Likewise, lobbyists and those doing business with the government may be subjected to lower contribution limits and other restrictions. (See Everyone Plays by Common-Sense Rules.)

Prohibitions on Contributions From Certain Sources

Because of concerns about large aggregations of wealth being amassed by corporations and the potential that such wealth will be used to corrupt officeholders, federal campaign finance laws prohibit corporations and labor unions from using their general treasury funds to make political contributions to federal candidates or political parties. In FEC v. National Right To Work Committee the Court held:

The first purpose of [prohibition on corporate and labor contributions and expenditures], the government states, is to ensure that substantial aggregations of wealth amassed by the special advantages which go with the corporate form of organization should not be converted into political “war chests” which could be used to incur political debts from legislators who are aided by the contributions. The second purpose of the provisions, the government argues, is to protect the individuals who have paid money into a corporation or union for purposes other than the support of candidates from having that money used to support political candidates to whom they may be opposed. We agree with the government that these purposes are sufficient to justify the regulation at issue.

At the same time, state and local regulation of corporate and union contributions to state and local candidates vary, with some states banning corporate and/or labor union contributions, while others limit such contributions or allow them entirely. However, even where corporations and unions are prohibited from making direct political contributions, they can set up PACs, which may be funded by individuals affiliated with the corporation or union.

Citizens United did not call into question the longstanding ban on corporate and union contributions to candidates.

As previously discussed, in Citizens United, the Supreme Court held that it was unconstitutional to prohibit corporations (and labor unions) from making independent expenditures, but did not call into question the longstanding ban on corporate and union contributions to candidates. Given the public’s reaction to the Court, allowing corporations and labor unions to make direct contributions to candidates only increases the public’s perception that our campaign finance system is riddled with opportunities for corruption.

There are a number of issues that should be considered when determining whether to prohibit or limit corporate and/or labor contributions to candidates. Among these are:

- Treating All Corporations the Same: Corporations are creatures of state law, which define the requirements to be a corporation and a corporation’s obligations to the state. However, federal law determines how a corporation is treated for certain purposes, such as paying federal taxes or involvement in federal elections. Corporations can take numerous forms, including for-profit, nonprofit and limited liability companies (LLC). Still further, corporations often have subsidiaries, parent corporations and sibling affiliates, all under common ownership. In addition, two or more corporations can come together as a joint venture or partnership, which is not incorporated. Any effective ban or limitation on the use of corporate funds to influence elections will have to take into account all of the different ways corporate money can enter the process.

- Other Forms of Corporate Support: Corporate support of candidates does not have to be in the form of a contribution of money to a candidate. Corporations may establish PACs to raise funds from certain employees to be contributed to candidates, hold fundraisers for candidates on the corporation’s premises and other “in-kind” support, help solicit contributions from their executives or employees and urge their employees to vote for a candidate. Some corporations are also involved in get out the vote activity. While it is clear that certain independent corporate activity is no longer subject to regulation after Citizens United, other forms of corporate support for election activity is still subject to regulation.

- Foreign National Corporations: Federal law and FEC regulations prohibit foreign nationals, including foreign national corporations, from contributing to any local, state or federal election and from making independent expenditures or electioneering communications. Some states have similar prohibitions. Therefore, even if a state does not have such a prohibition and does allow corporations to make contributions to candidates, a foreign national corporation cannot contribute in state or local elections. However, the FEC does not apply the prohibition to wholly owned subsidiaries of foreign national corporations, as long as no foreign national money is used to support the U.S. corporation’s political activity and no foreign national individual is involved in the decision making regarding such activity. Given this, extreme concern exists that the FEC’s rules do not really prevent foreign national involvement in U.S. elections. This should be a chief concern for any reform advocates, particularly in ballot initiatives where the FEC has ceded its regulatory power almost entirely.

Next Up: Models

Note:

On November 3, 2015, as this report was being finalized, voters in Maine and Seattle passed important campaign finance reform initiatives.

The Maine Clean Elections Initiative increases the amount of money in the Maine Clean Election Fund, requires entities making independent expenditures to disclose their top three donors on their communications, and increases the penalty for campaign finance violations.

The Honest Elections Seattle initiative establishes the nation’s first citizen funding program based on vouchers. All registered Seattle voters are given $100 worth of Democracy Vouchers to give to the candidates of their choice. Qualified candidates may redeem the vouchers with the city; to qualify candidates agree to spending and contribution limits and to participate in three public debates. The Seattle initiative also prohibits city contractors and entities that hire lobbyists from contributing to candidates.